|

Photograph from the Worcester News, December 1980, when an era was ending. One of the city's last remaining glovemakers, Miloré Ltd, was closing down. The company was founded in1934 and at its height employed 250 people.

|

||

James Ward

|

|

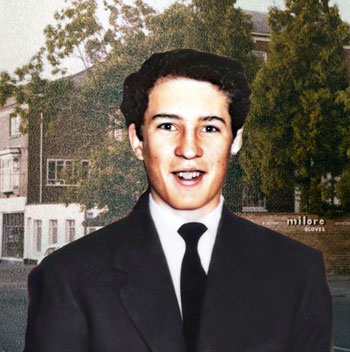

My brother Graham Holland was born 15th March 1942. He first went to Knightwick School, and then to Christopher White Head in Worcester. After finishing his schooling he started an apprenticeship at the Miloré Glove factory, at St George's Square in Worcester. There he not only learnt the skills in glove cutting, but found that he was a born natural at it, becoming one of the fastest cutters at the firm. He was skilled to the point that he could often produce an extra pair of gloves from a skin that he was given to work with, which obviously helped the firm and gave him more money,especially as the job was mainly piece-work; although they did have a standard rate of pay. His expertise and speed was well liked by the managers, but his shop floor workers often did not like that he was earning more than they were. |

Miloré also had a factory in Bromyard, there first one was at the top of Sherford Street, in 1946. Graham got married on the 18th December 1962, and went to live in Bromyard, where he bought a house and lived with his wife Lin and their two children Andrew and Sarah. It made it easier for him to be able to now work at the Bromyard Miloré Factory, and he stayed there with the company until the firm had to close in 1981. Graham knew Les Winfield well, and Les held out a life line to Graham and others who had now lost their jobs. Les would have liked Graham to have worked at his new premises, the old school at Crowneast. Graham however decide to work from his new home in Bromyard in Flaggoner's Walk, where he lived with his wife Ann and daughter Victoria, and take his finished cut gloves to the factory and pick up new leather to work on at the same time, which saved a lot of travelling. I can't remember the other glove company's that Graham worked for but there were definitely two others who he cut gloves for. Not all the leather he now worked with was the soft kid glove leather that Miloré had often used. So cutting the heavier leather pelts was a hard job. I watched him one day, the leather would be kept damp and wrapped up in a type of gauze. A skin would be taken out and the rest wrapped up again. Then Graham would inspect the skin for flaws and the areas that are blank where a leg would have been, this allowed him to access which point on the skin that he would start his first stretch from. The skin was stretched across the edge of his table at least twice, once each way, then he would place a card template on to the skin in the area that was best. This allowed him to use the large cutting scissors that were used for this. From the cut out he would stretch it back and forth again across the edge of his work bench, place the template on again, and tap it down to leave the marks to cut along and then cut it out. This piece was stretched again, the template pressed on it and then cut again. That was now one side of one glove cut. For a pair of gloves he would have to cut four of these and then the fourchettes, usually six per pair of gloves, sometimes thumbs as well. Just watching him doing the stretching needed for just one pair of gloves was when I realised how hard he worked every day. I can't remember how many pairs he cut each week but it was a lot. When he was given the skins they would tell him how many pairs they expected back from them, so when he managed to perhaps do a few extra, not only did he make more money, but so did the firm. Graham died on the 11th September, 1977 and is buried in the church yard at Bromyard. Les Winfield opened his glove factory Alwyn Gloves in 1963, and kept working there until his death, on the 24th November 2015, at Worcester Royal Hospital, aged 96. |

||

A much later addition to the Worcester Glove manufacturing industry, Milore glove factory operated from 1946 to 1981. It was the second-last glove company in Worcester, employing mostly women and young girls who had to undergo 6 weeks intensive training to qualify as a skilled glove maker. They were paid for each pair produced so they had to be quick and produce good quality gloves. Many women left the factory once they got married but many were able to continue to earn money by having a sewing machine at home. Being an outworker was a means of remaining employed after marriage. There was a strong community spirit amongst the employees who enjoyed staff trips to the seaside and who socialised outside of work by going dancing together. The company specialised in producing high fashion women's gloves, and commissioned up and coming designers to develop the appeal of a fashionable brand. The gloves and other artefacts such as photographs, leather colour cards, letters and glove patterns, were saved for future reference when the factory finally closed. The Museums Worcestershire archive collection contains numerous pairs of unworn Milore, brand-new leather gloves in an array of bright jewel colours, still in their cellophane wrappers. Gloves in a range of exciting colours including powder blue, fuchsia, buttercup yellow, and turquoise can be seen with a range of different pattern effects. Bows, embroidery, cut-out pattern effects, ruching, and many other intricate and unusual design details can be seen. In the early years the Bromyard factory closed for several weeks in September so the girls could go hop-picking with their families on the farms in the surrounding areas. There were staff trips to the seaside, Dudley Zoo and, in October, a weekend visit to see Blackpool's Illuminations that ended with dancing the hours away. |

|

|

In the 1940s, some Jewish refugees from Europe settled in Worcester. Emil Rich, a refugee from Germany, founded one of Worcester's last remaining glovemakers, Milore Glove Factory. Queen Elizabeth II's coronation gloves were designed by Emil Rich and manufactured in the Worcester factory. Milore Gloves, which is now a branch of Sainsbury's on Barbourne Road. These three companies employed many hundred Worcestershire people, but were far from the only glove works in town. In 2001, Worcester City was given the collection of Mr Robert Ring, a lifetime glove collector and the last managing director of Milore Gloves in Worcester. In 2011, his family also donated his archive of gloving ephemera and his research writing. By 2015, only one Worcester glove factory remained. Les Winfield established Alwyn Gloves at Crown East in 1963 and continued to manufacture high quality gloves in the traditional manner, purchasing his equipment from the larger glove factories as they closed down. Les refused to retire and was still working in his 90s, with customers that included Prince Phillip and Margaret Thatcher, and contracts to supply the space research industry. |

||

|

|

Gloves fit for a Queen. |

|

Worcester makes gloves that are literally fit for a Queen. In fact, Milore have just made two pairs which the association of glove manufacturers will give to her as a present. The city used to have 30 glove manufacturers but now there are just a handful left. The River Severn was supposed to be ideal for washing the skins but these days they are brought in dyed and ready to be used. Mr Kurt Helwing production manager, says that once workers have got through the four years apprenticeship they tend to stay for a lifetime because they are earning more than they can in some other industries. The problem is finding them to start with. TRAINING "When people left school at 14 it was easy to join us and be fully trained at 18. Now, with the school age at 16, by the time apprentices have finished they are over 20. Consequently, few are looking for this type of apprenticeship when they can get an unskilled job and earn more than they can at 16." He said. The firm employs some 70 people at its St. George Square factory, another 30 in Bromyard and a lot of outworkers, mainly married women who have left the firm to have children and who have machines at home. I expect you have noticed that when you put your hand into a glove it "gives" across the palm and not lengthways, that is where the skilled stretching and cutting comes in. They wouldn't be much good if you could only just get your hand into them and then the fingers stretched out of all proportion. And then on to sewing them together after they have been stamped out. It takes 26 weeks for a girl to learn the ins and outs of machining - quite a long time. Anybody can put a glove together but there's a difference between putting it together and making it." Added Mr Helwing. Some 60 percent of Milore's production is exported to Western European countries, America and Japan. |

|

Ray Wright ironing or more correctly, laying out, the completed gloves on equipment which dates from the First World War and which, within the industry, has not been altered. Royalty, film stars and air hostesses are just a few who put their hands into the firm's gloves. Did you know that Americans have shorter fingers than we have, or that Japanese have smaller hands? Norwegians look for warmer gloves while the conservative Swiss prefer theirs plain. The glove industry starts making its winter collection in March, when most of us are thinking about summer, and then its Spring gloves go into production in October. Mr Helwing says that fashion is very conservative at the moment and is not giving them a chance to make some of the more interesting colours and embroidery that they enjoy but he hopes things will improve soon. |

|

|

||

Hands up. Who's the last maker of gloves? |

||

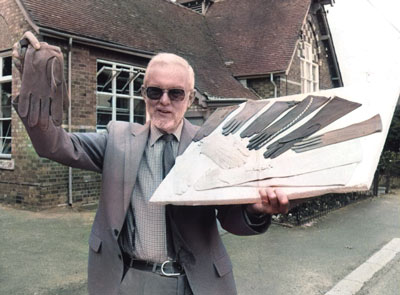

While motor factors and the building trade might decorate their storerooms with the latest calendar of Sun Stunners or Megan Fox in a hard hat and not much else, Alwyn Gloves went for comic opera. It was their end of the market. Firms like Fownes, Dent Allcroft and Milore employed many hundreds of people. Even in the 1950s, there were a dozen members of the local glove manufacturers association. Still operating from an old village school at Crown East – "full of period charm", an estate agent might say... "rather ramshackle" would be a more honest description – Alwyn is now Worcester's last remaining glove company. He said: "They tried bare hands, fabric gloves and rubber gloves, but nothing is as good as leather." However, there was a sign of the times at the recent royal nuptials. Lady Thatcher and Sir Cliff Richard are among other famous names to order from Alwyn and the company also supplies gloves for the aldermen of the City of London, who sit during court sessions at the Old Bailey Despite the Dickensian appearance of the little factory – Bob Cratchit wouldn't look out of place at one of the desks, if he could find room among the clutter – it does have a nod towards modern technology, at least as far as the internet is concerned. |

|

|

Les Winfield outside his premises Alwyn Gloves at Crowneast. [The old school where Les set up his business, and who my brother Graham Holland cut gloves for, after the closing of Milore] Now there is just him and Brian and the ghosts of times past. The small army of 80 outworkers, all women who sew the gloves together in their own homes, has been reduced to half a dozen. |

||

Death of Les Winfield aged 96 - Worcester News, 11th November 2015. |

|

The death of Les Winfield, who has died just two days short of his 96th birthday, is more than just the passing of one of Worcester's great master craftsmen. It also marks the death of an industry. Because Mr Winfield was the last man standing in the city's glove trade, which at one time totalled more than 150 manufacturers, employed 20,000 people and produced seven and a half million pairs a year. The two man band at Alwyn kept going until Mr Winfield succumbed peacefully in Worcestershire Royal Hospital, having only been admitted a few days before from his home in Rushwick. He died pretty much of old age, for he had no serious illness and drove his car well into his 90s, all the way down to Oxfordshire to deliver to his outworkers. Appropriately, his funeral service will be in Worcester Cathedral, on Tuesday, November 24 at 11.30am. Les Winfield left behind him a business caught in a time warp. But the Dickensian clutter of the little works on the western edge of the city could well prove an historical gem, because Worcester Civic Society would like to see it saved. The hey day of the Worcester glove industry was from the 1790s until the 1820s, but even when Mr Winfield set up Alwyn Gloves in 1963 there were a dozen members of the local glove manufacturers association. At its peak, his company employed a workforce of 50, including five specialist glove makers, and supplied gloves to Prince Philip for his carriage driving, Lady Thatcher and Cliff Richard, among a register of famous clients. When Prince Andrew married Sarah Ferguson in 1986, Alwyn was commissioned to make a pair of uniform gloves for the wedding. |

As foreign competition decimated the British glove industry, Mr Winfield kept his ship afloat by concentrating on the top end of the market and niche areas such as tight fitting gloves to prevent contamination of vital component parts in the munitions and space research industries. |